This blog is part of a series of posts about the ASOR and SBL conferences in November, 2018. They can be accessed at the IHARE website and will be posted to academia.edu.

One of the developments in the ASOR and SBL conferences was the increased archaeological data from the 11th and early 10th centuries BCE (Where Is the Tenth Century BCE?: The ASOR and SBL Conferences and The Tenth Century BCE and the SBL Conference). This development occurred even without any sessions on Khirbet Qeiyafa. One logical consequence to this development is the meaning for the biblical stories set in that exact time period. As previously reported, Mahri Leonard-Fleckman, begins her ASOR abstract “A Fresh Biblical Lens on the Iron Age Shephelah: Social Ambiguity versus Order in Judges-Samuel” with:

Textual studies of the Shephelah have yet to catch up with the archaeological portrait of identity ambiguity or “entanglement” in this Iron Age landscape of ancient Israel.

In her SBL presentation, (“Boundary Crossing and Boundary Blurring in the Bible’s Tales of David and Gath,” S19-117 Historiography and the Hebrew Bible), she suggests the book Memory in a Time of Prose: Studies in Epistemology, Hebrew Scribalism, and the Biblical Past by Daniel Pioske (Oxford University Press, 2018) is of value in understanding this subject. I downloaded, printed, and read the book. Chapter 2: Gath of the Philistines (85-133) and Chapter 4: A Past No Longer Remembered: The Hebrew Bible and the Question of Absence (182-191 on Khirbet Qeiyafa) directly relate to the question raised here. What follows is a review of these two sections and some thoughts of my own on the topic.

Gath

Based on his presentations in the preceding chapters, Pioske begins here by stating that Gath flourished prior to the emergence of a mature Hebrew prose. The result of this interpretation is the need to bridge the gap between these two time periods: the 11th-10th and the 8th BCE.

He begins his analysis with a reference to the Epic of Gilgamesh. At the beginning of the Epic and at the end of Tablet XI, Gilgamesh walks the walls of Uruk. He deems these lines as part of a sophisticated framing technique drawing on the images of Uruk’s monumental fortifications. The physical presence of the walls became part of the process through which the story of Gilgamesh was remembered. As he puts it:

…the historian must be sensitive to the possibility that memories from former times endured alongside the places to which they referred… (90).

Turning to the site in question here, Pioske observes:

There are nearly double the biblical references to this Philistine site, in fact, than to other settlements identified within the so-called Philistine pentapolis,,, (90).

These references to Gath in the Hebrew Bible are not mere data points or part of lists. Quite the contrary, the Gath occurrences are at key moments and play a significant role in the unfolding narrative. Pioske asserts that:

…it is unlikely that the scribes who made reference to Gath within their stories would have had access to first-hand, eyewitness information about the famed Philistine city…(91).

He concludes that:

…the biblical writers possessed knowledge about Gath that was reflective of the location’s early Iron Age past (91).

This observation leads Pioske to the crux of his investigation: how did scribes have access to material from decades if not centuries prior to the composition of the Gath stories.

To resolve this question, Pioske reviews the textual and archaeological information.

Philistine Gath in the Hebrew Bible (91-102)

What strikes Pioske’s attention is the military-basis for the Gath biblical mentions. Its battles occur in the heart of Benjamin/Judah/Israel. The Gittites are warriors. They are descendants of the Raphah which he compares to the Rephaim. In other words, the Gittites are part of a warrior cult of distinct martial abilities who are remembered for their prowess. David defeats them, is a vassal to them, and they serve as his mercenaries, quite a range of relationships one might add. Yet the reason for David’s attraction westward to Gath is never explained by the storyteller (97). Pioske concludes that “Gath likely functioned as a crucial gateway into the highland regions and the capital of Jerusalem” (101). Most important for the storytelling, there may even have been a time when Gath became part of Judah in the 8th century BCE just as Hebrew prose writing began to flourish (102).

Philistine Gath: The Archaeological Evidence (103-117)

In this section, Pioske describes the Gath landscape. He then turns to the Bronze Age archaeology noting Canaanite Gath’s contacts with Egypt such as in the Amarna letters. Next he notes the arrival of the Philistines in Iron I. He posits that native Canaanite population from the rural areas of the Shephelah came to be relocated in the Philistine-controlled cities (109). Pioske has no explanation for how and why Gath developed as it did during this time.

Shortly afterwards, nearby Judean cities begin to be built/rebuilt as well. He specifically notes the border town of Beth-Shemesh. Pioske is struck by the rebuilt and refortified Judean town of Lachish in the early ninth century BCE given its Late Bronze Age rivalry with Gath. These constructions plus the evidence of trade leads Pioske to conclude that relationships between Gath and its eastern highland neighbors in the tenth and ninth centuries BCE was peaceful.

Gath and the Resilience of a Remembered Past (117-131)

Pioske begins by asserting that “biblical scribes had access to information that could have only descended from the early Iron Age period… (118). Furthermore, Gath is always regarded as a foreign city even though Judah temporarily had some sort of control over it during part of the eight century BCE. The geographical setting also dates to the Iron I period due to the presence of Ekron as a significant city.

…in the thousand years that passed from the Middle Bronze Age to the end of the Iron Age, there was one and only one moment when both locations were of some size and status at the same time: the Iron I period, or the era in which the biblical writings indicate the importance of both (119).

There is no biblical account of Gath having been conquered by Israel or Judah. In addition its rise in Iron IIA coincides with the founding and growth of the House of David (123). All these developments are not by happenstance or coincidental.

Pioske now has to explain how this happened. He does not exclude the possibility of some older documents which mentioned Gath. He sees oral story-telling as being crucial to the maintenance of these memories. Nonetheless he is forced to conclude that “how and why this Philistine city was remembered with such tenacity remains something of a mystery” (125). He refers to other biblical examples of such memories at Shiloh, Bethel, and Tirzah. He notes non-biblical examples such as Troy, Icelandic sagas, and Beowulf enduring for centuries before being written.

His overall conclusion is:

…a remembered past endures more readily when it is tethered to the physical environs of a place (131).

For a short time, Judah controlled Gath. The visible remains endured.

…old memories of the Philistine center may have found their way into Hebrew texts because traces of this remembered past were still preserved in the ruins familiar to those who began to write these stories down (131).

Gath was a “place of memory.” Due to its sheer size it left an impression on the local inhabitants. And just as the Epic of Gilgamesh begins and ends in Tablet XI with the walls of the immense city of Uruk, so Pioske begins and end his chapter on Gath with references to Gilgamesh at Uruk.

Khirbet Qeiyafa (182-191)

Pioske’s analysis of this site is quite different from that of Gath – it’s all archaeology, there are no texts. He describes the site through its uniqueness.

Indeed, at a time when the eastern Shephelah and highland regions consisted of mostly small, unwalled villages and a limited population, the fortifications of Kh. Qeiyafa offer an unanticipated testament to political will and human capital at this point along the Elah Valley. The sophisticated casemate wall construction of the settlement and its two monumental gates would have been a tremendous undertakings for this period in time…(186).

Nonetheless, this extraordinary site garners no biblical mention.

The lack of reference to this location is all the more mystifying considering that a number of events within Kh. Qeiyafa’s vicinity are recounted in the biblical narrative and are said to have occurred at that moment in the early Iron Age when Kh. Qeiyafa was most likely populated and functioning… (191).

How Come Gath Is in the Hebrew Bible and Khirbet Qeiyafa Is Not?

My explanation for this discrepancy is human agency, specifically that of Abiathar. To repeat the approach I have taken in Jerusalem Throne Games and in these blogs

1. Abiathar is the father of the alphabet prose narrative.

2. Saul’s desire to become king was the catalyst for his writing.

3. All his writing was political: not historical, not theological, not as literature.

4. He wrote throughout his life from the time of Saul to Solomon.

5. To identify and date his writings permits a better reconstruction of Israelite history and the development of the Hebrew Bible.

6. He had rivals, a successor, and a student.

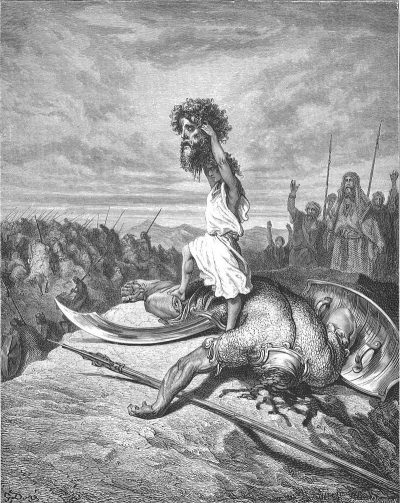

So now let’s apply the Abiathar template to the question of Gath and Khirbet Qeiyafa using the story of David and the Philistine warrior written in the time of Ishbaal and now in I Sam. 17.

1. The story originated as a standalone story. In the early part of his career, Abiathar had not yet mastered the skill to write continuous prose narratives.

2. Abiathar employed nameless individuals to represent a people. These anonymous people may be considered a diagnostic for his prose. In this case the Philistine warrior represents the Philistine people especially those warriors Pioske referred to.

3. Since the Philistine warrior is a symbol the story should not be taken as a physically literal encounter. Think of the story of “Ronnie and the Bear.” Ronnie goes hunting for a bear and at the end of story either is rocking on his bear skin rug and/or is sitting under his stuffed bear trophy. Older people will know that Ronald Reagan was a real person, the Soviet Union was real, and that “Ronnie and Bear” is about the United States winning the Cold War. They will not try to analyze the weapon Ronnie used or identify the species of bear he hunted. Younger people might be clueless and condemn Ronnie for killing an endangered species. “David and the Philistine Warrior” is not about a literal encounter; it is a political polemic by Abiathar about who has the right stuff to go into the arena and defeat the enemy.

4. Long before Thucydides put words in the mouth of Pericles, Abiathar put words in the mouth of David.

5. Khirbet Qeiyafa is not the only thing missing in the story, so are Jonathan and Ishbaal. Even if Saul did not confront the Philistine warrior, how come neither Jonathan nor Ishbaal did either? Abiathar is going for the kill. Saul, Jonathan, and Ishbaal all lacked the right stuff. At this time, Saul and Jonathan were dead and Ishbaal was weak. The story is an all-out humiliation of Benjamin and its leaders by the Philistines.

6. As I was thinking these points through, it suddenly occurred to me to ask where did Saul and Jonathan really die? The idea that the Philistines and Benjaminites squared off far to the north of where they both were located seems a little strange. It makes much more sense that the fight to the death occurred right where the two peoples faced in other: in the Elah Valley. Khirbet Qeiyafa was Saul’s pride and joy. The Philistines defeated Saul and destroyed his fortification. In other words, Abiathar located his political allegory at the site of Benjamin’s greatest humiliation.

When this thought flashed through my mind, it stunned me. To substantiate it will require analysis of other stories especially involving Jabesh-Gilead in Judges and Samuel. Still given the premise that stories are political allegories and not history, the showdown battle in the Elah Valley makes a lot of sense.

7. As much as Abiathar enjoyed mocking the Benjaminite warrior prowess, David was a wiser politician. He knew he could not have a kingdom with a hole in middle. He knew that Benjamin had to accept being part of the kingdom of Israel under the rule of David if it was going to work. It was probably at that point that Abiathar developed the David and Jonathan episodes. He now had learned how to write a continuous narrative of multiple episodes.

8. Biblical scholars have observed the similarities between the stories of Hector and Achilles and David and the Philistine warrior. They are deliberate. Why assume Israelites were the only intended audience? Abiathar’s story was for the Philistines too. When they heard the story they expected to be the winner. After all, they were like the Mycenaeans from across the waters and they had defeated the Benjaminites at Khirbet Qeiyafa. Naturally they would have expected the Achilles figure to be triumphant in Abiathar’s story.

Abiathar apparently deployed an old Israelite motif: take the defining story of you enemy and reverse it. In the Song of the Sea, the gift of the Nile is defeated by flooding waters. In the Song of Deborah, the wilderness woman smites Pharaoh Se-se III, a reversal of Pharaoh smites the male enemy. Now Abiathar had used the same technique against the Philistines.

This realization means the Philistines probably brought the story of Hector and Achilles with them when they arrived in Canaan after 1177 BCE. So how did Abiathar learn it? Obviously he did not go to Philistine scribal school. The most reasonable answer is through, Anson Rainey forgive me, the tribe of Dan. Dan was the first Sea People to arrive. It joined the Israelite-led anti-Egyptian NATO alliance (see Deborah at the SBL Conference). It was inducted into the Israelite community. And it had stories of Hector, Achilles, and then Samson. Imagine that. The Hebrew Bible helps prove antiquity of portions of what became the Iliad! That will drive the minimalists crazy.

The application of the Abiathar template provides a richer, fuller, more coherent account of early Israelite history and the development of the Hebrew Bible than possible with the present paradigms. Plus it is a lot of fun. Abiathar’s first stories will be the subject of my presentation at the upcoming Mid-Atlantic SBL conference.