Even as colleges are in turmoil from coast to coast, the 250th anniversary of the birth of this country looms closer and closer. Whether or not we will be one country as we exist now remains a debatable question. Whether or not We the People will want to celebrate the birthday remains problematical … at least for segments of the population. Still there is a federal commission dedicated to that celebration and the situation is becoming dire at the federal level even as some grassroots efforts continue to move forward.

Things keep happening and not happening. The easiest way to tell that the Semiquincentennial has not yet entered the mainstream consciousness of the nation is that it has not yet been politicized. Neither the MAGA nor the Woke have had much to say yet about the 250th. It still has not been weaponized. How long that will last is hard to determine. One way to gauge the absence of politicization is the absence of action at the national level.

NATIONAL LEVEL

Let’s start with an urgent request just received from the American Association for State and Local History. If you are a history organization you may have received this notice multiple times already as I have.

Dear Colleague,

I am reaching out today with an urgent request, one AASLH rarely makes. We need you to reach out to your Senators to help secure major, new federal funding for the work of history organizations.

For the last several months, AASLH has met with many Congressional offices to advocate for substantial federal investments in the nation’s history community to support the commemoration of the America’s 250th anniversary. At the local, state, and national levels, the Semiquincentennial presents an opportunity to engage all people in a whole, complete American history, one that tells everyone’s story and emphasizes our historical and ongoing efforts to become a more perfect union.

As part of these efforts, we are working with a bipartisan group of lawmakers in both chambers to circulate a “Dear Colleague” letter that calls for robust funding in support of 250th activities across different federal agencies, including the Institute for Museum and Library Services, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Endowment for the Arts, the National Park Service, and more. The Senate letter is general in nature and nonpartisan, designed to garner the support of the largest possible coalition of Congressional members.

We need your help! We ask that you contact your Senators to encourage them to sign on in support of this letter. Constituents influence their Members of Congress most directly, so your participation is critical.

This is an urgent request. With the anniversary now just two years away, the next federal budget will be our last opportunity to secure meaningful new funding to support our work in the lead-up to 2026 and beyond.

Here’s what we need you to do:

1. Use this spreadsheet to find the email addresses of the Legislative Directors for your state’s Senators.

2. Use the draft message below to craft an email to your Senators’ Legislative Directors. Please use the subject line: “FY25 America 250 Senate Sign-on Letter.”

3. Download this “Dear Colleague” letter and include it as an attachment in your email.

Please note that the draft message below includes a “Quill Link” for the convenience of the Senate offices. These links only function for people with a Senate.gov email address. Although the link won’t work for you, it will work for the Senate staff that you are contacting.

AASLH has been working with The Normandy Group on this effort; please do not hesitate to reach out to me or either Christine Pellerin (cpellerin@thenormandygrp.com), or Phil Powell (ppowell@thenormandygrp.com) know if you have any questions.

Thank you for your support of this effort.

Best regards,

John Dichtl

President & CEO

dichtl@aaslh.org

EMAIL FROM CONSTITUENTS TO SENATE OFFICES:

Dear [INSERT NAME],

On behalf of [INSERT ORGANIZATION] based in [INSERT CITY AND STATE], I’m contacting you to urge Senator [INSERT NAME] to sign onto a Dear Colleague letter led by Senators Shaheen and Cramer in support of America 250 activities. The fast approaching U.S. Semiquincentennial (America 250) is just over two years away and is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to remind Americans of the ideals of our nation’s founding, including freedom, liberty and justice. The FY25 appropriations process is the last real opportunity before July 4, 2026, for Congress to provide funding to support America 250 activities across agencies which invest in local organizations like mine and are charged with carrying out programming for this purpose.

Please use the following Quill Link to sign on to the letter. Additionally, please do not hesitate to contact Ted Trippi (Ted_Trippi@Shaheen.senate.gov) or Michael Helmer (Michael_Helmer@Cramer.Senate.gov) with questions.

Thank you for your consideration of signing onto this letter.

Best regards,

[INSERT NAME]

On the one hand, it is good to see a national organization taking the lead to advocate for the 250th in the halls of Congress. On the other hand, it is sad to see that the situation has become so desperate. Note the urgency of the request. This year will be the last year to request funding in time for the celebration in 2026. Think of the pipeline for military arms to Ukraine. It isn’t as if one day the bill is authorized by the President and the next day, American arms magically appear on the frontlines to hold off the Russian onslaught. Funding takes time.

Organizations are planning now for upcoming events. They cannot take for granted how much will be funded at the federal level, how much will be allocated to the individual states, and how the states will establish mechanisms and protocols to enable grass root history organizations to tap into the federal funding.

Keep in mind that the federal 250th organization is scheduled to close up shop after the July 4, 2026, show in Philadelphia anyway.

STATES AND THE 250TH

Connecticut

Semiquintentennial planning makes progress at Declaring Freedom Conference

Declaring Freedom, a four-day conference at Central Connecticut State University, was a resounding success with a Keynote from Governor Lamont, and four days of students, teachers, historians, academics, and colleagues from the history and museum community coming together to debate, discuss, and learn from each other about how Connecticut will commemorate this event in 2026. Hosts included CT Humanities, the The America 250 | CT Commission, the Association for the Study of Connecticut History, and the CT Council for the Social Studies.

Massachusetts Office of Travel & Tourism: 250th Events Calendar

The planning for Massachusetts’ commemorations of America’s 250th is in full swing, with lots of meetings and coordination within Massachusetts and across state lines. The MA250 logo was revealed for the first time at the Governor’s Conference on April 2! Please send any events to be added to MOTT’s statewide calendar for the 250th Anniversary of the Revolution in Massachusetts to Sheila Green.

NEMA Conference Call for Proposals

Session Proposal Deadline: March 29, 2024

We the Museum: Toward a “More Perfect’ Vision for our Changing World 2024 Annual Conference will be held November 6-8, 2024 in Newport, Rhode Island.

As we approach America’s 250th anniversary, now is a time to reflect on both the origin of America’s museums, and consider the field not only in its current state, but where it has grown from the past, and what it can be in the future. Learn more about the conference, and session proposal topics, as well as session proposal brainstorming sessions at the link below. Questions? Email Jenn Wilson at jennifer.wilson@nemanet.org.

Vermont’s 250th Anniversary Commission

Governor Phil Scott has signed an executive order creating the 250th Anniversary Commission to plan, coordinate and promote observances and activities that commemorate the historic events associated with the American Revolution in Vermont.

The year 2026 will mark the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the formation of the United States of America. Vermonters played a significant role in the colonists’ assertion for independence from Great Britain, from the Green Mountain Boys successful assault at Fort Ticonderoga to the Battle of Hubbardton, and to the Battle of Bennington where Vermont troops helped defeat a British force to set up the victories that turned the war in favor of the new Americans. Events and education will continue with commemoration of the 1777 campaign and the founding of Vermont.

To observe these events, Vermont will be joining other states and partners to encourage remembrance of our past, commemorate the present and look forward to a promising future.

Read the full Press Release here: 250th Anniversary Commission Press Release

Our Mission

Vermont’s 250th Anniversary Commission will inspire all Vermonters to learn from the history, legacy, and context of the past to build strong Vermont communities for the future. Through collaborative local and statewide initiatives that explore an inclusive history of the American Revolution, Vermont 250 will support and encourage the preparation, planning, and execution of programs and events that examine a formative period of our nation and how it continues to shape our culture and values.

250th Anniversary Commission Strategic Plan

Vermont’s 250th Anniversary Commission has compiled a reading list related to the events, people, and places of the American Revolutionary War-era and Republic of Vermont. This is not a comprehensive list but one source for materials related to this significant period on our state’s and nation’s history.

Reading list for American Revolutionary War-era and Republic of Vermont.

If you are interested in having your community or organization events endorsed by the 250th Commission, please complete this form and submit for evaluation. Please submit events at least 6 weeks before it is scheduled to begin. Endorsed events will be included on the Vermont 250th Anniversary calendar of events.

Tell us how you wish to commemorate the 250th. We want to hear your ideas for events, activities, educational opportunities, discussions exploring our complicated history, re-enactments, anything!! Please email us at SOV.Vermont250@vermont.gov

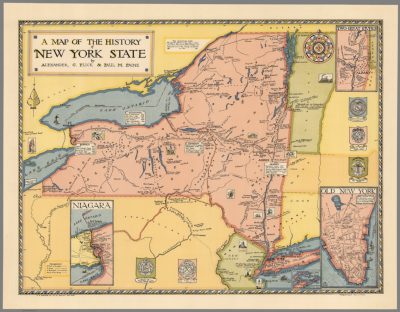

New York

And then there is New York. New York provides an alternative view to the actions of these other states.

There is a State Commission and there has been one for years. Unfortunately even after years, it is not yet fully staffed and has yet to conduct its first meaning. It appears that the people who have been appointed are taking matters into their own hands. A meeting will be held at the New York State Museum in Albany on the morning of May15. A public meeting will be held in the afternoon.

Did I mention that the State has yet to fund the commission?

This dismal state of affairs is not matched on the local level. There are counties, towns, and cities acting on the behalf of the 250th. There are too many of them for me too list them or to search the web for them. That would be one of the responsibilities of the state commission: simply to track what is going on in the state.

Good thing for New York, so much of the American Revolution occurred after July 4, 1776. That deadline then is not the cutoff for events in the state; it is just the beginning.

HAPPY 250TH 1774

All this focus on 1776, should not cause us to lose sight of what happened 250 years this year. It wasn’t as if the Boston Tea Party occurred in December 1773 and then people went into a deep freeze until the Battle of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. The year 1774 was a pivotal one in the shifting of the mental maps of the colonists from being loyal to King George III to being patriots on behalf of a newly emerging entity. It was the time of the First Continental Congress when steps were taken to mark this shift.

It’s already too late for federal support for the events of 1774. It probably is too late from New York State support as well. It is up to the grass root organizations in all the states to take the lead in recognizing that the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution already is underway.