On May 15 of this year, I was hit with an historic preservation tsunami. It was totally unexpected. It occurred so quickly and powerfully I scarcely realized what had happened. The source of the tsunami was the Sunday New York Times. It was not one article. Instead it was a series of independent articles that when combined hit me with the force comparable to when individual snowflakes band together and become a snowball.

I should explain these comments by stating that I read the newspaper while holding it with two hands the way it is supposed to be read. I do not read every article, especially on Sunday, but by turning each page I see more than I would online and read more. The unexpected juxtaposition of articles powerfully drove home a message about land use and displacement that called to mind what had happened centuries earlier although without the violence this time.

A CATSKILLS ESCAPE, REFRESHED WITH A CAN-DO SPIRIT

This article was about Melissa Gilbert and Tim Busfield finding a home for themselves in Highland Lake, New York, in Sullivan County, the Catskills. The article told the story of this Hollywood couple finding a home for themselves in a place where they had never sought to look before. What they found was a somewhat rundown structure with potential. They call it a “the cabbage,” a combination of “cabin” and “cottage.” The article recounts the efforts of this one couple to fulfill the potential of this one structure and its grounds. Naturally this adventure is chronicled in a new memoir by Gilbert entitled Back to the Prairie: A Home Remade, a Life Rediscovered.

So far this is the story of a single couple on a single piece of land that respects the land and the surrounding community. However the story does not stop here.

RURAL PRESERVATIONISTS LOSING GROUND:

A squabble over a luxury development upstate reveals a shifting of priorities among local leaders

The stakes are more serious here. The article begins with the town supervisor in Durham, NY, firing the chair of the Durham Historic Preservation Commission. How often do you see that happen? And from a voluntary position!

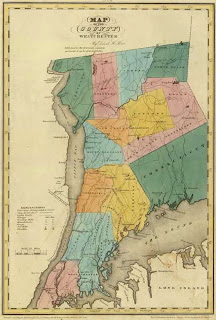

The catalyst for this termination is a real estate project in Greene County, NY, where the actual city of Catskill is located, north of the area traditionally known as the Catskills today. Specifically, this rural enclave of 2700 people were faced with a 95 acre project. Woods, wetlands, and stone outcroppings were to be transformed into 12 luxury homes. Isn’t that progress? Undeveloped land is going to be developed. Isn’t that was has been going on since the Europeans first arrived here?

The historic preservation committee thought otherwise. It wanted a more in-depth environmental study. What it got was public meetings lasting past midnight with tempers raised followed by a lawsuit and the firing. After the dismissal of the commission chair, three sitting members resigned in protest.

As everyone reading this blog undoubtedly knows, the Gilbert/Busfield example above is one mere drop in a flood of people from the city seeking refuse from Covid and urban life in second homes or new first homes. Naturally also, developers are responding to meet the housing needs of this new population. Such development also increases the property tax base. Naturally, these developments have “put intensifying pressure on the historic preservation commissions of these towns and cities.”

The scale of this development exceeds that of the Gilbert/Busfield renovation of an existing property. In this instance, an undeveloped area in the historic hamlet of Cornwallville would become a large-lot subdivision with cul-de-sacs houses starting at $1.6 million. There would be a small farm house aka community center (for the 12 homes).

A neighbor of the prospective development says: “It’s a gated community, without the gate. This is about stewardship of nature, stewardship of historic architecture, and about preserving open space.”

A group of concerned neighbors and residents formed the Cornwallville Residents for Rural Preservation. They fear the dozen homes “will wreak havoc on the area’s fragile ecosystem and that the developer lacks experience to undertake a project of this size.” As another neighbor says, “We are a simple people here; we don’t need these fancy houses and a homeowners’ association. It will bring lights and noise. They are building on wetlands; it just isn’t right.”

The long article begins on the front page of the Metropolitan section and continues with a full page in the section. The article then cites the dismissal of the vice chair of the Kingston, NY, historic preservation commission, in Ulster County just to the south of Greene County. In that case it was over a plan to bring 140 apartments and 420 parking spaces into a historic district dated to 1658. The remainder of article covers a related situation in Poughkeepsie, NY in Dutchess County on the east side of the Hudson River from Ulster County. The Poughkeepsie Historic District & Landmark Preservation Commission of seven people is in a precarious position as well – the terms of three of the seven positions have expired with two more to go this summer. Here the mayor does not need to fire anybody, only to wait.

In these conflicts between commissions and the local governments they serve, the commissions have tended to be the loser.

THE HAMPTONS

There are five articles on the Hamptons in this once section of the May 15, 2022, New York Times.

Establishing a Beachhead for Modernism: Timothy Godbold, an interior designer based in Southampton, became a preservationist after learning so many houses constructed in this style have been torn down

He watched his architectural world being destroyed before his very eyes. The problem was widespread as routine demolition was underway “to make way for sprawling new mansions.” He sought out like-minded preservationists only to learn that no such organization or group existed. As a result he became a Hamptons preservationist. The existing Village Board of Architectural Review & Historic Preservation commissioned him as a journalist to write a report on the historical significance of the property.

When you think of historic preservation, do 20th century buildings come to mind? Sarah Kautz, preservation director at Preservation Long Island observed that municipalities are ill-equipped to deal with such recent buildings, meaning those built when you were alive so how could they be historic? Paul Goldberger, former architecture critic of The New York Times, bemoaned the destruction of modest great midcentury homes to build McMansions. 20th century architectural history (middle class) is being lost to create 21st century development homes for the wealthy. Progress has come to the Hamptons!

A Cute Place to Live (if you can Find a House for Sale)

This article is about living in Cutchogue on the North Fork of Long Island. The image used is The Cutchogue Diner which I used in my previous blog about diners. According to the article “Affordable housing and land preservation are the issues that make headlines most often in the local paper, The Suffolk Times. Congrats for having a local newspaper! Apparently long-time residents are being priced out of the community.

A Local Broker Who Is Also a Television Personality: JB Andreassi, of ‘Selling the Hamptons,’ says low inventory has toughened the market

The comment that stuck with me separate from SELLING THE HAMPTONS is selling the Hamptons. “The other thing is, we actually show the Hamptons. We show the local places, like the barbershop — the kids who run that barbershop grew up in East Hampton — and Hill Street boxing, founded by a local Southampton kid. I love that we are bringing exposure to places like Golden Pear café, the mom-and-pop shops that make the Hamptons so distinct.”

Millionaires Vs. Billionaires: The East Hampton Airport is set to close Tuesday, but frequent fliers, business owners an others have filed lawsuits to keep it open.

Here is a problem you do not see often. The front page of the Real Estate section shows people disembarking from a helicopter at the airport. The front-page headline is “HIGH-END PROBLEMS: The rich and the very rich battle for air supremacy, pitting Hamptons homeowners against helicopter service.” The article gets a pull page and half a second page on the inside. Forget about the middle class travails.

Battlelines have been drawn. On one side there are the residents living below the air routes who “are besieged by egocentric helicopter and private jet passengers who don’t care about the toll their commute takes. On the other side are the aforementioned highfliers plus “the salt-of-the-earth locals concerned for their businesses.” The clash reflects “the changed identity of the Hamptons over the past decades; it has gone from elite seaside hideaway to glitz-stuffed scene.” As a resident since 1955 said:

We went from wanting to get more and more people out here visiting, and more and more income, and more and more well-to-do money to save the place. Well, that happened. Now the problem is, are we going to lose what they came out here to see — the windmills, the beautiful vistas, the sunsets, the beaches, the quiet?”

As the billionaires fight the millionaires who fought the middle class and year-round residents over the land and lifestyles one witnesses a four-dimensional archaeological tel of multiple strata, peoples, and cultures. One could write a history of the 20th and 21st centuries in the Hamptons based on these conflicts. But what about the people before the Hamptons became the HAMPTONS?

Ma’s House Fulfills a Grandmother’s Dying Wish: A Shinnecock Nation home is host to a residency program, workshops and exhibitions

Below the half-page continuation of the billionaires versus millionaire article, there is this article about the Shinnecock Nation reservation to the west of Southampton Village. This new addition to the landscape is an art studio in progress. The artwork can be in the style of the Plains Indians as well as Shinnecock. The work explores the cultural significance of the Shinnecock Nation’s history in the Hamptons according to Yaya Reyes, the founder of the Art & Soul: Hamptons festival. Does historic preservation include the Shinnecocks who preceded the billionaires, the millionaires, the middle class, and the English?

In this tsunami of preservation articles in a single issue of the newspaper, one comes face to face with multiple issues over land, lifestyle, displacement, development and progress. In the previous centuries these areas in the Catskills and the Hamptons have been buffeted by numerous changes. Peoples have been displaced; ways of life have disappeared or vanished in mere relics of once thriving vibrant communities. How would you like to be a middle-class family grilling hamburgers on July 4 only to have a tour bus stop to take your picture as a quaint example of a once common way of life?

There are two unrelenting factors in the constant push for development in the name of progress … besides those very values. The first is numbers. When people just keep coming and coming and coming, the people who are already there can become lost and overwhelmed in the process. Think of how the Great Migration from the South now dominates the Middle Passage people population in the north over those who are descendants from colonial people. The wave of people migrating from the city has yet to crest. People can work from anywhere and fall in love with what the rural areas have to offer … as long as they are fully connected, can easily travel to the city, and have all the chain stores necessary for a civilized life.

The second factor is money. The situation is limited to people wanting to move to these areas but often to have second homes there. Communities of second homes, week-end homes, summer homes create a different dynamic. College towns experience something similar with the peregrination of youth. The millionaires and the billionaires present a whole new challenge to historic preservation to say nothing of the social fabric of a community. It is still true that people do not want to lose their land and their way of life. We have the opportunity now to witness and perhaps experience personally something similar to what happened centuries ago but without the violence.