This blog is part of an ongoing series about the presentations in the annual conference of the American Historical Association in January, 2025. This blog focuses on the American Revolution. Snippets from the new documentary were previewed.

The Plenary Sunday January 5 8:00-9:30

American Revolution-A New Film Directed by Ken Burns, Sarah Botstein and David Schmidt. Written by Geoffrey Ward

1. Jim Grossman, Executive Director AHA, announced that Ken Burns will partner with AHA for local screenings.

2. Lauren DuVal, University of Oklahoma characterized it as a scholarly work.

3. Brown referred to the American Revolution as a bitterly polarized time.

4. Ken Burns called it a civil war and not a sectional war. There were patriots and loyalists throughout the country unlike the more sectional confrontation in the second civil war. The documentary filmed many battles. Burns called it the most consequential revolution in human history.

5. Alan Taylor, University of Virginia, noted the patriots were a diverse military force fighting together in behalf of something in which they really believed.

6. Geoffrey Ward simply referred to it as a brutal vicious war.

State of the Field for Busy Teachers: Eve of American Revolution

AHA Session 263

Sunday, January 5, 2025: 3:30 PM-5:00 PM

Chair: Karin Wulf, Brown University and the John Carter Brown Library

Panel:

Mary Beth Norton, Cornell University

Samantha Futrell, Virginia Council for the Social Studies

Benjamin L. Carp, Brooklyn College, City University of New York

Tracey Prince, East Orange STEM Academy

Session Abstract

We are now in the midst of local, state, and national celebrations marking the 250th anniversary of the independence of the United States. This panel highlights the pivotal years of 1774 and 1775, as the lines of division that defined the American Revolution took shape. What can classroom teachers learn from recent scholarship about the opening chapters of the American Revolution? What sources and perspectives can help students engage with this history? And how might teachers navigate political pressures around the significance of the founding era?

The AHA’s State of the Field for Busy Teachers series provides a forum for history teachers at all levels to interact with leading historians and discuss content, sources, and trends in scholarly interpretation on a theme related to topics commonly addressed in the history classroom. We invite leading historians to outline current debates, new lines of inquiry, useful primary sources, historiographic developments, and/or revised periodizations. For the rest of the session, a panel of educators moderates a discussion, with robust audience participation, about how to incorporate insights from new research into the classroom. We anticipate a lively exchange in which all participants can walk away with new insights and resources.

General comments from the session included:

1. What can we do about the Trump impact?

2. The Revolution created opportunities and possibilities for immigrants.

3. The debate on the cause of the Revolution started with the Revolution itself.

AHA Session 89

Women in Revolutionary-Era New York City: Opportunities and Consequences

Saturday, January 4, 2025: 10:30 AM-12:00 PM

Chair: Serena R. Zabin, Carleton College

Panel:

Charlene Boyer Lewis, Kalamazoo College

Lauren Duval, University of Oklahoma

Carolyn Eastman, Virginia Commonwealth University

Alisa J. Wade, California State University, Chico

Session Abstract

A thriving commercial and cultural hub in the revolutionary era, New York City functioned as the British army’s North American headquarters for the majority of the American Revolution as well as the first capital of the United States. The experience of daily life in revolutionary-era New York therefore offers a unique perspective on the war and the nation that emerged from it.

Throughout the imperial crisis, and later, as war descended upon the city, New Yorkers experienced novel, often disorienting and frequently violent changes to their daily lives. Prewar boycotts and food shortages introduced new pressures into daily life. Once the war was underway, armies brought diseases and increased the potential for violence. In occupied New York, British troops and their families intermingled with civilian inhabitants, including New Yorkers of various statuses, races, and political affiliations, loyalist refugees from throughout the colonies, and enslaved freedom-seekers. Within the occupied city, property destruction and theft were rampant. Quartered troops disrupted the routines civilian households. Yet, amid this disruption, life went on. Families adapted to wartime constraints, adjusting their budgets and modifying their strategies of financial management. Businesses and labor markets rebounded. Neighbors looked out for one another.

But in addition to the perils of garrison life, it also introduced new possibilities, especially for women. Enslaved women flooded British garrisons in search of freedom for themselves and their kin. As the favored social companions of British officers, young elite white women wielded enhanced levels of social power within the garrison. Other elite women, benefiting from the privileges of from their status, whiteness, and familial ties, harnessed kinship-driven commercial networks to maintain financial security, and even profit, throughout the revolutionary period. And as diseases ran rampant, both during the war and into the yellow fever epidemics that occurred in the early years of the republic, many poor women found financial security in their work as nurses, and continued to benefit from visibility and respect these labors earned them. The opportunities and consequences of the war years continued to resonate far beyond the conflict and into the early years of the nation.

Throughout the revolutionary era, women—Black and white, free and enslaved, loyalists, revolutionaries, and disaffected—were integral to daily life in New York City. Their experiences illustrate the daily, quotidian experience of the American Revolution and the revolutionary era and demonstrate both the opportunities and the consequences that it introduced into people’s lives. Exploring diverse women’s experiences, this roundtable will explore how centering these perspectives sheds new light on revolutionary and founding-era New York City in ways that illustrate the centrality of gender to this period and this place.

1. What had NYC learned from 1793 Yellow Fever outbreak regarding quarantines and the myth of black immunity.

2. The male death rate doubled that of women in NYC.

3. The demographics of the city changed with 30,000 men descending into the city. It became more cosmopolitan. There were interactions between the British officers and the American women who remained in the city. The American males couldn’t compete with their British counterparts and American women adopted European styles versus the American plain-style.

– long tenure of British

– Dutch law differed from British law and American law on the treatment of women.

– There were differences between the elite women in the city and patriot women outside the city.

– The Revolution happened in the houses and on the streets and not just on the battlefield.

Q&A The question was raised about the impact of fire which burned the city.

Earthly Bodies, Heavenly Bodies, Bodies Politic: Conceptualizing Republics and Their Defenders in Europe, Britain, and America

AHA Session 153

North American Conference on British Studies 2

Saturday, January 4, 2025: 3:30 PM-5:00 PM

Chair: Rachel J. Weil, Cornell University

Session Abstract

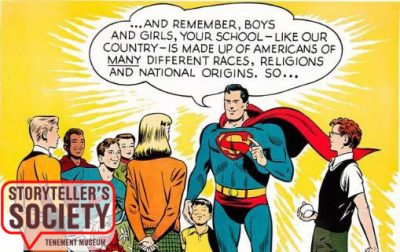

Those who defended and crafted republics in Britain, America, and Europe drew upon a vast range of languages and conceptual vocabularies to define republicanism, forge political unions, and warn of the dangers of excess and fanaticism. This panel offers a comparative perspective of the long republican tradition, emphasizing the vigorous and energetic analogies and metaphors that writers adopted in the early modern and modern period to defend republicanism as a political system against monarchism, fanaticism, or corruption. As each paper demonstrates, the “languages” and discourses which shaped republicanism included broad influences past and present; whereas early modern writers in Britain and America adopted medical and cosmic ideas of cooperation and citizenship to champion republican ideas of liberty, modern writers seeking to combat fascism revived republican languages previously mired in debates over commerce, enlightenment, and war. Through this range of case studies, the panel shows how a classical mode of thinking – republicanism – became conceptualized and communicated in new political contexts.

The Star-Spangled Republic: Cosmic Republicanism, the American Revolution, and Beyond

Eran Shalev, University of Haifa

From the fifty-star flag to the Great Seal, from Greenbacks to the Star Spangled Banner, the star-as-American state, and consequently the United States as a constellation of star-states, is arguably the most salient – and least explored – symbol in American public language. The configuration of the star-as-state, and the consequent image of the United States as a “new constellation,” emerged in the early days of the American Revolution. The republicanism and anti-monarchism of the Revolution shattered the traditional political view based on the imagery of a single solar power center, habitually associated with monarchical systems. Instead of the king as Sun around which the political realm revolves and which holds the nation in equilibrium, in the 1770s an alternative and revolutionary republican cosmology emerged and was enshrined in the new nation’s symbols: a diffuse constellation of uniform floating stars devoid of a solar center that embodied egalitarian and republican values. The American Revolution would thus give rise to new modes of understanding and communicating the political order: no kingly star overshadowed and dominated others; together they constituted a novel federal republican system in which a plurality of individual stars held together, comprising a unity that was more perfect than its discrete parts.

Throughout the republic’s founding, expansion and the consequent addition of stars to its spangled banner, when it temporarily collapsed during the Civil War – and beyond, the language of political astronomy provided a distinct and rich vocabulary to articulate and express contemporaries’ shifting attitudes toward, and understanding of their federal republic. This unique, prevalent and overlooked language enabled contemporaries to communicate their positions regarding state and society, justify and vindicate their republicanism, and express their doubts regarding the fate of the United States.

What Do We Do When Liberty Dies? Republicanism and Fanaticism after Enlightenment

Richard Whatmore, University of St. Andrews

Most republics owe their origins to the perception that liberty has been lost and that action needs to be taken to restore or create anew such liberty. In the eighteenth century most of the surviving republics or free states – Venice, Genoa, the Dutch Republic, Geneva, the Swiss Confederation (and some would include the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth) – were seen to be losing their liberty and no longer had the tools to do anything about it. They gradually lost their independence in the turn to empire that accompanied what Hume termed commerce becoming a reason of state. For most republicans in the eighteenth century, the doctrine looked as if might go the way of the dodo; it appeared unsuited to commercial society, enlightenment and the large states generated by the necessity of expanding markets. The irony is that republicanism not only survived but thrived to become the foundational ideology of free states. This paper explores the republican legacies of the two free states that reversed the association between republicanism and military defeat: Britain and the First French Republic. Each accused the other of fomenting fanatic forms of liberty, addictions to war and empire and the renewal of wars of religion via republican patriotism. In the 1940s, Hayek, Popper, Talmon and others were searching for tools to combat fanaticism in the form of fascism, in the contested republican histories of the eighteenth century. They were certain that tools to prevent the death of liberty in the present could be found in the intellectual history of the European past.