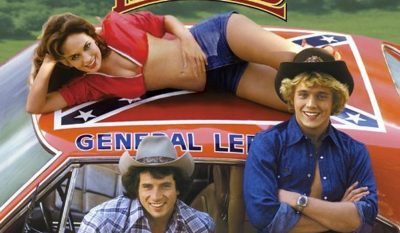

The Dukes of Hazzard was a very popular TV series that ran from 1979 to 1985. It was a cleaned-up version of an outlaw family in Georgia. By “outlaw” one should think of moonshine, racing fast cars (later NASCAR), and a general disdain for the law. It featured, besides the prerequisite babe in short shorts, a car called General Lee with a Confederate flag painted on the roof. Surprisingly, this top-rated show for seven seasons engendered no “cancel” culture outcry. America was different then. The outcry did not happen until after the Charleston church shooting in 2015 when the show was in reruns.

The Dukes’ good ole boy lifestyle may be said to be generally reflective of a distinctive folkway in American culture. It is a folkway that does not take kindly to being told what to do and resents the people who tell them, that is, the “dam Yankees.” The odds are the Dukes in real life would not and are not vaccinated. It would be interesting to speculate if they would be vaccinated if the TV show was still being produced and the outcry if they were.

Diverse America includes the Scotch-Irish, a people often overlooked given the racist standards of today. I wrote about this diversity back on August 28, 2018, in “Fellow Americans” versus “Tribal Rivalries”: Whither America?. The blog featured the work of David Hackett Fischer and Colin Woodard. Those sections are reposted below.

DAVID HACKETT FISCHER

On an academic level, I became more aware of the diversity of the United States through Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America by David Hackett Fischer. As the title indicates, the book divides the English or British into four distinct groups of folkways. He identified them as:

The Puritans who famously settled in Massachusetts and the surrounding areas

The Quakers who tended to be limited to one colony, Pennsylvania

The Cavaliers who started in Virginia but spread to other southern colonies

The Scotch-Irish who tended to be located in the border lands, the back country or fringe areas.

So rather than view the people from Great Britain monolithically, one should understand them as four distinct peoples or folkways.

These folkways brought their lifestyle with them when they emigrated to the colonies. Fischer lists various characteristics by which he defines each folkway in the area of Great Britain where they lived. Then he traces each characteristic or its equivalent to the life they created when they arrived here. In general terms, Fischer finds they each folkway transplanted their way of life from the old world to the new. Thus to claim that the English settled America obscures the reality of the situation – four different peoples [from there] settled here.

Fischer continues the story beyond the colonial era. He tracks the migrations of these peoples across the United States as it expanded westward. Most famously are the New Englanders who became Yorkers around the time of the Erie Canal. They kept moving west across the northern portion of the country. Their distinctive trait was doing something they already had done in the 1600s in New England – start a college.

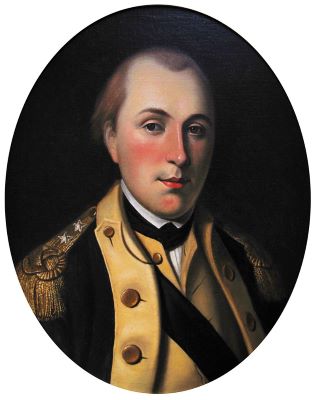

He concludes by identifying the folkway to which the individual American presidents belonged. The early domination of the Cavaliers (Virginians) and New Englanders (Adams father and son) are obvious. Today we have no appreciation for the significance of the election of Andrews Jackson, the first of many Scotch-Irish presidents. Now he is just a dead white male; back then he was our first diverse president.

COLIN WOODARD

Recently, Colin Woodard, has continued this line of thought. He is the author of American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. As the title suggests, his purview extends beyond the four folkways analyzed by Fischer. Woodard certainly is aware of Fischer’s work and he has expanded on to reflect the greater diversity which exists today. On July 30, in an opinion piece for the New York Times, “The Maps That Show That City vs. Country Is Not Our Political Fault Line: The key difference is among regional cultures tracing back to the nation’s colonization,” Woodard applied his template to the recent presidential election.

[O]ur true regional fissures can be traced back to the contrasting ideals of the distinct European colonial cultures that first took root on the eastern and southern rims of what is now the United States, and then spread across much of the continent in mutually exclusive settlement bands, laying down the institutions, symbols and cultural norms later arrivals would encounter and, by and large, assimilate into.

In other words, New York is still a commercial city (thank you Dutch) and Boston is still a college city thank you Puritans).

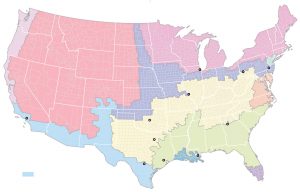

His analysis tracks 11 different groups.

Tracing our history, I’ve identified 11 nations, most corresponding to one of the rival European colonial projects and their respective settlement zones. I call them Yankeedom; New Netherland; the Midlands; Tidewater; Greater Appalachia; Deep South; El Norte; the Left Coast; the Far West; New France; and First Nation. These were the dominant cultures that Native Americans, African-Americans, immigrants and other vital actors in our national story confronted; each had its own ideals, assumptions and intents.

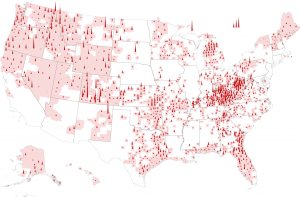

Through a series of colorful maps, Woodard then compares the vote percentages from 2016 to these cultural demographics. His explanation for the stark differences he finds in each of their choice of presidential candidates is:

Why the differences? I’ve long argued that United States politics resolves around the tension between advancing individual liberty and promoting the common good. The regional cultures we think of as “blue” today have traditions championing the building and maintenance of free communities, today’s “red” ones on maximizing individual freedom of action. Our presidential contests almost always present a clear choice between the two, and the regions act accordingly.

Take a simple and well-known example not in the article: healthcare. The “individual freedom of action” or “don’t tread on me” faction despises being told what to do and having no choice about it. Whether a law is in their best interest is secondary to whether it is being imposed on them by condescending arrogant self-righteous elitists or not (the 2010 election). And why should the Democrats try reasoning with such people in the first place? As Junior Trump said, they are not even people. Oh wait. He was talking about the Democrats. How can there be “come let us reason together” when neither side can acknowledge the humanity of the other?

JOE KLEIN

Joe Klein joined the discussion in an essay October 17, 2021 in The New York Times entitled appropriately enough “The Four Americas: Why the past is never past” (print, the online version is Joe Klein Explains How the History of Four Centuries Ago Still Shapes American Culture and Politics on October 4.

He begins by noting that as he watched the COVID crisis enfold, he thought back to Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. In his comment on the Scotch-Irish “wild caste of immigrants,” he links them to the January 6 insurrection and the Whiskey Rebellion fought by their ancestors against the Constitution.

However, Klein is troubled by the fact that America includes many other folkways besides ones identified by Fischer. For one thing, he does not appear to be aware of Woodard’s 11 groupings. He also does not seem to recognize the acculturation or assimilation which can occur once a person from one folkway grows up in the world of another folkway. On a slightly different note, think of the independent countries today where judges wear the trapping of British judges.

In any event, Klein is somewhat optimistic. He comments that each of these different groups “provided an essential strain of the American idea.” This concept puts him at odds with The New York Times 1619 Project which in practical terms is oblivious to these different white folkways and operates under the Woke racist idea that if you’ve seen one white person, you’ve seen them all. By contrast, Klein opines these tensions among the folkways “created a distinctive American spirit. That defines us, too.”

Individually and collectively, these analyses suggest there is little likelihood the Scotch-Irish folkway or those who grew up in that culture will ever voluntarily agree to be vaccinated. Perhaps a charismatic Scotch-Irish President like Andrew Jackson could persuade them that it is in their own best interest to be vaccinated. After all this folkway traditionally has disproportionately served in the military which requires obedience in a structured setup. But neither the former nor the present President are capable of providing such leadership.

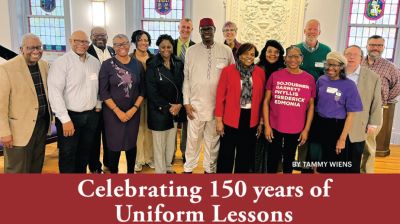

Perhaps if future Hall-of-Famer and Superbowl-Winning quarterback Aaron Rogers had strongly advocated for vaccination instead of playing cutesy-wootsie hide-and-seek about his status, these people would have listened to him. But Rogers failed the country in his moment of truth and Joe Rogan did not die from COVID either. At this moment in time, there does not seem to be a charismatic leader in the Scotch-Irish tradition who can pierce the bravado of the folkway which would rather die than listen to reason from the Puritan elitists symbolized now to them by all people by Anthony Fauci.