The Bible Among Ruins:

Sodom, Israelite History and the Hebrew Bible

ASOR

November 20, 2025

Peter Feinman

What is the soul of the Western tradition? Argument. Socrates goes around Athens investigating the claims of the supposedly wise and finds that the people who claim to know things don’t. The Lord threatens to destroy Sodom for its alleged wickedness, but Abraham reproaches and bargains with Him — that for the sake of 10 righteous people He must not destroy the city.

In both traditions, Athens’s and Jerusalem’s, the lone dissenting voice is often the heroic one (“Our Vanishing Culture of Argument,” Bret Stephens, op-ed New York Times Sept. 16, 2025, print).

We here an example of the popular view of the Story of Sodom and Gomorrah. Of course, the very names “Sodom” and “Gomorrah” also are well known in American culture. Even “pillar of salt” is familiar. From Abraham’s dialog with God to the cosmic destruction of a city, this one short story has left an indelible mark in the American culture. These are examples of how names and events can become part of the cultural legacy to people who never even read the Bible.

“The Bible among ruins” is a phrase used by Dan Pioske in three connected books to examine the impact of physical ruins in the landscape in which Israel lived on its history and in writing Hebrew Bible. He focuses on ruins west of the Jordan River. One ruin which he does not include in his study is Sodom, its location still a matter of debate. It is generally located east of the Jordan River either at the south end of the Dead Sea or the north. This paper will address the possible impact of the ruins of Sodom regardless of its location on the writing of the Hebrew Bible and Israelite history even though no Israelites lived among those ruins and Israel did not exist when Sodom was destroyed.

As Pioske observes, biblical writers lived in a world that already was ancient. The lands familiar to them were full with the ruins from people who had lived up to two thousand years earlier. References to these ruins abound in the Hebrew Bible, attesting to widespread familiarity with the material remains by those who wrote the biblical texts. Never, however, do we find a single passage that expresses an interest in digging among these ruins to learn about those who lived there before. That does not mean stories were not told about the ruins the Israelite people encountered or heard about.

In this book, Pioske offers a study of ruination in the Hebrew Bible. Drawing on scholarship in biblical studies, archaeology, contemporary historical theory, and philosophy, he demonstrates how the ancient experience of ruins differed radically from that of the modern era. For biblical writers, ruins were connected to temporalities of memory, presence, and anticipation. Pioske’s book recreates the encounters with ruins as it was experienced during antiquity and shows how modern archaeological research has transformed how we read the Bible.

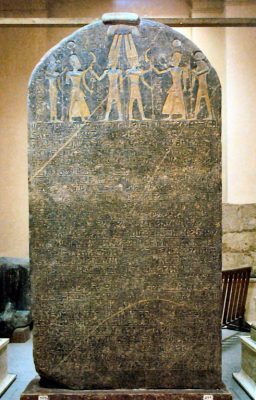

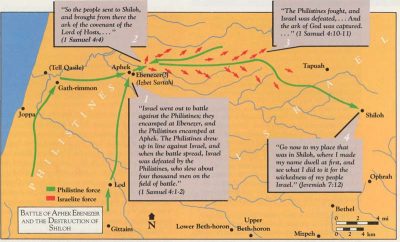

I propose to modify Pioske’s approach to divide ruins into two categories – the cosmic and the human. The human-caused ruins are the focus of Pioske’s study. They include such well-known sites as Shiloh which is included and Mount Nebo which is not. The ruin of former where the ark of Yahweh was located is attributed to the Philistines based on the biblical account. The latter where an altar to Yahweh was located at the burial site of Moses is attributed to Mesha based on the stele which bears his name. Two of the leading cosmic-caused ruins are Sodom and Jericho. This paper concerns the cultural legacy of the ruins of Sodom, location not known

The challenge is not to find Sodom. Instead is to understand how biblical writers used the physically real places including ruins to craft stories relevant to the times in which he and his audience lived. We are a story-telling species and the stories we tell have to be credible to the listeners. As Pioske points out with numerous examples from the Early Bronze Age, Middle Bronze Age, and Iron Age, there were physical places the ancient Israelites could see in the course of their daily lives crying out for explanations as to how that ruin came into existence. Pioske is more concerned with ruins from the time and place of Israel itself like Shiloh. However that does not mean the cultural landscape of Israel is restricted to the political landscape. The political landscape changed over time with conquests by Assyria, Babylonia, and Persia. Even before such conquests, in the Bronze Age, Israelites and Canaanites were aware of a world beyond the Jordan. Canaanites knew there was or had been a vibrant world east of the Jordan.

Ruins need to be brought to life if a story is to be told. Otherwise an archaeology field report would be sufficient. Stories involve people. That means it is virtually impossible to prove the truth of the ruins stories of the Hebrew Bible. A second complication is that the stories were not composed to be physically literally true. They were not business contracts.

Even non-biblical stories may be politically derived. See Baal and the Politics of Poetry by Aaron Tugendhaft (London; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018). Biblical writing is political in nature, especially the stories. See Literature as Politics, Politics as Literature: Essays on the ancient Near East in honor of Peter Machinist edited by David S. Vanderhooft and Abraham Winitzer, (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2013). They were not written as history, literature, or theology but about current events regardless of the time in which they were set. The stories, especially the ones we continue to tell today, are about the political world of the author.

To understand a story, one must put it in its political context. Therefore attempts to prove biblical stories physically literally true are as misguided as the efforts to prove them false also are. At the SBL conference last year, Tamara Cohn Eskenazi delivered the presidential address entitled “The Bible in Politics and Politics in the Bible,” subsequently published in JBL 144:1.

In the published version, she cited The Beginning of Politics: Power in the Biblical Book of Samuel by Moshe Halbertal and Stephen Holmes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), In God’s Shadow: Politics in the Hebrew Bible by Michael Walzer (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012) and an online course by Jacob L. Wright “The Bible’s Prehistory, Purpose, and Political Future,” (Coursera, first offered in 2014) among others. The point is well-taken. The stories of the Hebrew Bible should be understood in their political context. That means understanding the historical context. The question is not where is physical Sodom but where is cultural Sodom. With Sodom we have the opportunity to examine how a biblical writer crafted a story based on known place names to deliver political messages at the time of the writing.

The quest to prove the truth of biblical stories has led to misguided efforts based on the presumption that the stories are meant to taken as physically literally true. The ongoing search for the ark on Mount Ararat is one leading example. The Mount Ebal Inscription discovered in 2019 is a more recent example. A third example included a presentation here at ASOR involving Sodom.

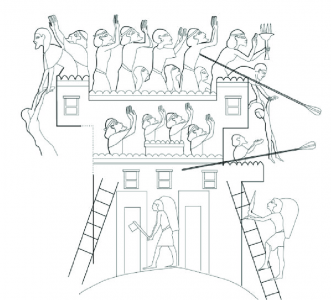

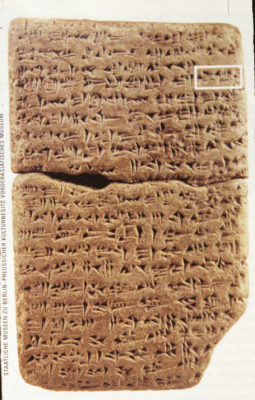

The specific ruin in question from the presentation is Tall el-Hammam. It was proposed that a meteor exploded at low altitude with the force of a ten megaton atomic bomb at an altitude of about one kilometer over the northeast corner of the Dead Sea. It obliterated all civilization in the 25-kilometer-wide circular plain that constitutes the “Middle Ghor.” A thriving city from Chalcolithic times to the Middle Bronze dominated the region as perhaps the largest city in the southern Levant. And then it was no more, conspicuously absent from the Middle Bronze Age Egyptian records of execration texts, Late Bronze Age conquest lists, and diplomatic correspondence. The researchers presented preliminary findings on the subject at the annual ASOR meeting in 2018.

Unlike most if not all other presentations at the ASOR conference, this one garnered media coverage. It did so because of words not mentioned in the presentation: Sodom and Gomorrah. As you might expect, the press coverage tended to focus on whether or not science had proved the biblical story true.

A fuller explanation appeared in Scientific Reports in September 2021: “A Tunguska sized airburst destroyed Tall el-Haman a Middle Bronze city in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea”. The parallels to the 1908 Siberian event was critical to the alleged Tall el-Hamman event. Over the next few years there were multiple revisions to the original article. Since that time the methodology, facts, and analyses of the presenters have been challenged over that comparison and the impact of the air burst. As a result the original article has been retracted by editors of Scientific Reports in April 2025, after the original version of this paper was written. So while the Siberian-parallel airburst hypothesis seems to have died, the issue of a suddenly ruined city remains.

It appears that goal of the presenters was to prove the Hebrew Bible physically literally true;

Then the LORD rained on Sodom and Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the LORD out of heaven; Genesis 19:24.

Gomorrah does not even appear in the heart of the story itself. To me that suggests that Gomorrah was an addition to the original story. In other words, the story of Sodom in Gen. 18 and 19 can be considered a literary tell with multiple authors. To understand the story, each stratum needs to be understood within its own political context.

Archaeology is of limited value in the reconstruction of the stories. After all suppose one did find irrefutable evidence that Tell el-Hamman or some other city was Sodom, so what? That would not prove the identity of any of the biblical characters, the alleged dialogs, or any of the specific events. Ur existed but that does make the biblical stories of Ur physically literally true. Haran existed but that does not make the biblical stories of Haran physically literally true either. Closer to Israelite home, the same can be said for Hazor and Shiloh.

I propose here to present the original Sodom story before the supplemental strata were added. I am guided by the politics template previously discussed. The location of historical Sodom is secondary to the political message by the creator of the story set in a ruined city. There is a three-part process involved here.

- Oral Memory (shared) – This means people remember a place or event without any story being associated with it. People remember Pompeii/volcano and Titanic/iceberg without remembering any story. Once a story is set there, the audience would understand immediately what the end result is going to be. I shudder to think that people watching the movie Titanic needed spoiler alert warnings because they didn’t know what was going to happen. My reading of the story of Sodom is that the writer and the audience were familiar with the name “Sodom” and that there was a pre-Israelite story or memory associated with it: a flourishing city that was suddenly and dramatically destroyed.

- Oral Story (created) – At a specific time and place, someone decides to tell a story derived from the shared oral memory of a place. I propose the original story of Sodom is about events in the present of its creation set in the past. All nameless people in the telling would have been known to the audience. The proposed root story-line of from the beginning of Genesis 19 then would be something like this.

- There are two unnamed messengers of Yahweh – the audience would have known who in the present they were.

- Lot as king, sitting at the gate of the city, offers hospitality – the audience would have known who in the present he is.

From there it is all downhill for Lot.

- Lot is a weak king.

- Lot cannot control his men (the military).

- Lot cannot protect his people (the women).

- The two human messengers warn Lot that his city will be destroyed.

- The two human messengers offer Lot and his family safety.

The original story ends there.

One was not expected to play a guessing game trying to identify the people involved. The audience knows who Lot represents and knows that Lot is loser in this story of power politics.

Is it possible to identify the historical context in which the story of Sodom was first communicated? It is not warrior poetry (Poetic Heroes: Literary Commemorations of Warriors and Warrior Culture in the Early Biblical World, Mark Smith, Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2014). It is not a savior judge story. It is not part of an extended narrative. There is no temple in the story. There is no Jerusalem in the story. The story functions in a context where there is one weak king of Israel and two messengers of Yahweh about to end his reign while offering to save him. I suggest the timeframe for the story is II Sam. 3-4, when David and Ishbaal clashed for the throne of Israel. It was the time of Joab, the warrior David could control, and Abner, the warrior Ishbaal could not control. It also was a time of messages being sent back and forth between the two camps. The story of Sodom suggests that David offered Ishbaal an olive branch before his untimely death.

This interpretation has multiple implications:

- the battle for the throne of Israel in II Sam 3-4 with multiple names and intrigues may indeed be a fairly reliable account what actually transpired. Histories of early Israel and the monarchy need to be pushed back to before the time of David and Solomon to the time of Saul and these eye witness accounts.

- what would become biblical writing existed in the time of the early monarchy starting in the time of Saul and certainly in the time immediately after his death

- stories may not be about the time in which they are situated. The story of Sodom should not be dated to the Patriarchal Age or the Middle Bronze Age in which it was set but to the time of David and Ishbaal when it was created.

- The original story of Sodom was pre-J and pre-Abram making it one of the earliest narrative prose stories. It occurred during the transition from warrior poetry and prose narratives about David’s rise to power. It is a primary source document from the 10th century BCE. There are multiple such stories from this transition period but Sodom is the only ruin story among them.

- Biblical writers could write physically literal (II Sam. 3-4) and symbolically or allegorically.

There any additional stories about Ishbaal expressed through the figure of Lot but they are outside the scope of this paper.

- Stories could be amended or supplemented. Gomorrah was not part of the original story. Lot’s wife was not part of the original story. Lot’s daughters were not part of the original story. Those writings occurred in other political contexts outside the scope of this presentation.

Abraham does not appear in the original story of the destruction of Sodom either. The genre has changed here. The story of Sodom may be considered a textual tel which can be excavated.

Sodom – legacy of a great Middle Bronze Age urban destruction

Story of Sodom – David and Ishbaal

Dialog between Abraham and God – performance by David and Abiathar as part of a larger royal ritual performed in Jerusalem

Supernatural Story of Sodom – Gomorrah, blindness, destruction, pillar of salt

Lot’s Daughters

Whereas the original story was a message between David and Ishbaal, the famed dialog was part of a royal performance performed at the capital. The story is not a primitive anthropomorphic relic from the primordial Israelite religion past. Quite the contrary, a real live flesh and blood human being was performing in the role of Yahweh.

He knew he was not Yahweh.

The audience knew he was not Yahweh.

But the audience believed the person spoke on behalf of Yahweh.

That means most likely the human performer was a priest, a priest of Yahweh.

In my opinion, the most logical candidate is Abiathar.

His performance provides a different spin to the dialog. Keeping in mind that the stories are political, the performance by an anti-Saulide priest of Yahweh prior to the story of the destruction of Ishbaal’s capital, makes the dialog about the lack of anyone righteous in the city extremely derogatory against Saulides. In fact, it represents a complete condemnation of the line. One should keep in mind the following exchange from 2 Samuel 16:5. 2:

5 When King David came to Bahurim, there came out a man of the family of the house of Saul, whose name was Shimei, the son of Gera; and as he came he cursed continually. 6 And he threw stones at David, and at all the servants of King David; and all the people and all the mighty men were on his right hand and on his left. 7 And Shimei said as he cursed, “Begone, begone, you man of blood, you worthless fellow! 8 The LORD has avenged upon you all the blood of the house of Saul, in whose place you have reigned; and the LORD has given the kingdom into the hand of your son Absalom. See, your ruin is on you; for you are a man of blood.”

This is a different kind of ruin. Power politics at the dawn of the Israelite monarchy was a blood sport. David was very proficient at it and we have the stories.