“Amelia Edwards:

The Founding of the Egyptian Exploration Fund and the Exodus

Peter Feinman

Institute of History, Archaeology, and Education

feinmanp@ihare.org

SBL

November 23, 2025

Amelia Edwards was the driving force behind the creation in 1882 of the Egyptian Exploration Fund (EEF, now Egyptian Exploration Society). The story of this individual is a remarkable one in its own right. As a woman of no money, no family connections, and no formal training in Egyptology who had spent decades of her life in totally unrelated activities, her formidable presence in the world of Egyptology would have been a surprise to those who had known her. She later would be referred to as the “Queen of Egyptology.”

In this presentation, I will examine the life of Amelia Edwards at the dawn of Egyptology and how quickly things changed after she died. She engaged in a variety of activities.

Great reader and enjoyed travel books: “devoured” Sir John Gardner Wilkinson’s Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians

Life-long love of theater from accompanying her mother there

First wrote a story at age four and had a poem published at age seven

Devoted her life to music from age 14 to 21

Performed in family theatricals and musicals

Journalist

Muralist: “The Landing of the Romans in Britain”

Novelist: heroines as a prelude to admiration of Hatshepsut?

Opera singer

Painter and sketch artist

There was nothing in her life then too suggest a future life in Egyptology or interest in the Bible. Then in 1871, the remedy for whatever personally was oppressing her was to go abroad. The travels of the next two years were to be crucial. Through them she achieved the distinction she had sought from girlhood though not in a way she could have anticipated.

Her first foray was to an area not normally associated with exotic travel – the Dolomites in Italy. Her travel book originally published as A Midsummer Ramble in the Dolomites (1873). Dolomites then were a little known area of northern Italy without the roads and hotels of tourism later built there. This area not far from the center of the Roman Empire was considered terra incognita for European travelers then.

Her second foray was a life-changing and unexpected trip to Egypt. She had not planned to travel there. Ironically thanks first to Napoleon exposing the area to Europeans and then to the steamship, Egypt was much more accessible than the Dolomites had been. There already was a standard tour package to and from the Second Cataract with great views of Abu Simbel. The land of Goshen was not part of these tours. She did not take a packaged tour but traveled privately. The trip was biblical to her:

“It is all so picturesque [used 34 times], indeed so biblical, so poetical, that one is almost in danger of forgetting the places are something more than beautiful backgrounds, and the people are not merely appropriate figures placed there for the delight of sketchers, but are made of living flesh and blood, and moved by hopes and fears and sorrows, like our own (201).

The example of Hatshepsut inspired her.

Queen Hatasu has been happily described as the Queen Elizabeth of Egyptian history; and she was undoubtedly one of the most extraordinary women of the ancient East (261).

…she proven herself to be one of the most magnificent builder-sovereigns of Egypt (268).

…it was to the genius and energy of this extraordinary woman that Egypt owed that great work of canalization which first united the Nile with the Red Sea.

Edwards described her as an ancestress of M. de Lesseps. She adds a huge footnote to her 1877 publication on the recently completed Suez Canal. She likened Hatshepsut to an explorer like Napoleon.

She subsequently spent years researching Egypt before publishing her book. During that interval she spoke with the archaeologists in Egypt and corresponded with Egyptologists. That research put her in the forefront of Egyptology as it existed then even though she had no formal education.

Edwards was trying to succeed in a man’s world. Her moment of truth came when she read and reviewed The History of Ancient Egypt by George Rawlinson. I have a copy of his translation of Herodotus. Clearly he was at the pinnacle of knowledge of the classical world including Egypt…except he wasn’t.

In a book review from August 6, 1881, for The Academy, Edwards wrote:

That Canon [of Canterbury] Rawlinson has read and carefully read, a great many works indispensable to a correct understanding of certain periods and events is undoubtedly true; but he has left unread full three-fourths of the literature of his subject.

Turning to chap. X., on “Religion,” we find our author absolutely unacquainted with nearly very new light which has been thrown upon the subject within the last seven years.

Nowhere does Canon Rawlinson’s defective equipment betray itself more unfortunately than in his biographies of the gods.

Indeed we have rarely met an author who is so little in love with his subject.

To go on multiplying instances of this kind would be a useless and ungrateful office. [OUCH!!] Canon Rawlinson is a distinguished Greek scholar, with an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of ancient Greek literature; but the time is past when Greek scholarship was a sufficient qualification for the task he has undertaken.

She was writing in time when the issue of the validity of the biblical text was being called into question. The selection for the professorship of Hebrew at Oxford College was part of this struggle. Driver and High Criticism won this round and Sayce went off to Egypt.

Edwards had already written a detailed letter on April 24, 1880, to The Academy identifying the site of Raamses. That letter led to her authoring a series of articles on Ramses and the Exodus. The series was anticipated in Knowledge with some short announcements about what was to come.

In an early number, probably the next, an important series of papers by Miss Amelia B. Edwards, the eminent authoress and Egyptologist, on the question, “Was Rameses II. the Oppressor of the Hebrews” will be commenced. (Knowledge, May 12, 1882, 583).

In the next volume will appear the first of a most interesting series of papers by Miss Amelia B. Edwards placing beyond dispute or cavil the identity of the Pharaoh of the Oppression. (Knowledge, May 26, 1882, 617).

One must keep in mind that the academic journals we associate with Egyptology did not exist. Publications like the Academy and Knowledge were the way to reach the educated population on a range of topics.

It is possible that the discovery of the mummy of Ramses II triggered the series in a time of heightened interest in him. Her series consisted of 16 articles from June 2, 1882, to Jan 19, 1883, on the subject of Ramses as the Pharaoh of oppression. Chronologically, she started with Joseph possibly under Hyksos Pharaoh Apophis in the attempt to fill the story of the 430 year Hebrew sojourn. She subscribed to the common and still widespread view of the Hyksos as a foreign barbarian horde who had conquered Egypt and from whom Egypt needed to be delivered. This misguided 18th Dynasty/Manetho perception continues to plague Egyptian scholarship. That period was a dark void crying out to be filled. She saw archaeology as being the key.

We have, at all events, the evidence of the Book of Exodus, and the testimony of several Egyptian documents, to show that, from the time of Ramesses II, when the new “treasure-city” was built and Goshen city ceased to be the chief town of the province, the old name of the Nome fell into either partial or complete disuse and the “land” or county of Goshen came to be called after its new capital, “the land of Ramesses.”

The article with these words was entitled “IX.- The Land of Goshen.” This area including the Wadi Tumilat was the focus of the effort to locate the route of the Exodus. In fact the first excavation authorized by the EEF was to find that route in that Wadi.

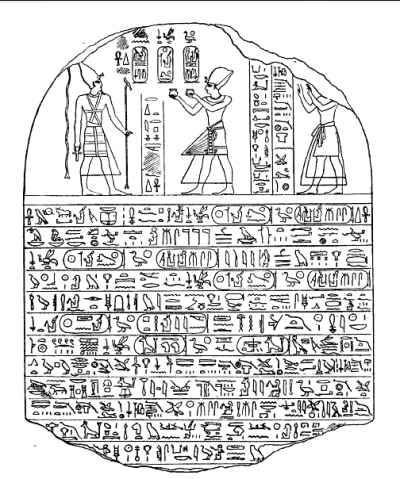

Edwards initially wrote before such discoveries as the Amarna Tablets, the Merneptah Stele, and the Bietak excavations. It is interesting to read her forcefully stated views based on the information she had available to her. One wonders what impact such discoveries would have had on her thinking. Still the importance of this 16-article Exodus series from 1882 by a leading Egyptologist should not be overlooked. It contains an in-depth analysis of the search for the Exodus based on the existing knowledge in 1882. It is a window into the state of the field at that time, possibly one of the longest reports written on that topic. It is unfortunate that the series is scattered over multiple issues in small print of a non-academic publication. The field would be well-served if those articles were extracted and bound in a single larger-print easily-accessible pamphlet or small book. It is an example of the how the Exodus in Egyptology is minimized.

It was in this context that the Egyptian Exploration Fund was created on March 30, 1882.

A society has been formed for the purpose of excavating the ancient sites of the Egyptian Delta…The general plan drawn out has received the approval of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Bishops of Bath and Wells, Durham and Lincoln, the Chief Rabbi, Archdeacon Arson… The founders are not the names one associates with the founding of an archaeology society. It does however reflect the mission of the organization. (Egyptian Exploration Fund 1882, 8).

That mission was clearly stated by the EEF. Find Goshen and the missing 400 years of the Hebrew sojourn.

Yet here [at Zoan-Tanis] must undoubtedly lie concealed the documents of a lost period of Bible history⸺documents which we may confidently hope will furnish the key to a whole series of perplexing problems.

The position of the Land of Goshen is now ascertained. The site of its capital, Goshen, is indicated only by a lofty mound; but under this mound, if anywhere, are to be found the missing records of those four centuries of the Hebrew sojourn in Egypt which are passed over in a few verses of the Bible, so that the history of the Israelites during that age is almost blank (Egyptian Exploration Fund 1882, 8).

The co-founder of the EEF, Reginald Stuart Poole, published then Cities of Egypt. He came from a more formal background and worked for the British Museum. His role is routinely overlooked. His 30-year academic record shows a great interest in biblical subjects but is outside the scope of this presentation.

In her review of Poole’s publication, Edwards wrote:

Remembering the enthusiasm excited by the discovery of the Chaldaean Deluge-tablets [Gilgamesh Epic], one asks with wonder how that enthusiasm is compatible with our indifference to the far more momentous discoveries which await the Egyptian explorer…Such records are more vitally important than all the Deluge legends recently collected from every corner of the globe….

[I]t is first of all needful to wake the Bible-loving, church- and chapel-going English people from their long sloth, and to make them see that now, if ever, it is a serious duty, and not a mere archaeological pastime, to contribute funds for the purpose of conducting excavations on a foreign soil. … (The Academy, December 2, 1882, 389).

WAKE UP PROTESTANTS. FIND THE EXODUS. This was a call to arms.

Poole celebrated the discovery of “the very walls on which the enslaved Hebrews worked…It is the first step towards delineating the route of the Exodus” (1883). The bricks might even be for sale until he realized how big they were.

So it should be no surprise that the first archaeology campaign funded by the EEF was to find the route of the Exodus. And lo and behold. It succeeded: The Store City of Pithom and the Route of the Exodus by Edouard Naville (1885). That publication became part of the Egyptological discourse as scholars debated the validity of the claim. One facet of the debate was how far north the Gulf extended and its possible connection to the Wadi Tumilat. They really struggled to find a scientifically-based understanding of Ex. 14-15 based on the actual topography of the land. The point is here is not whether any given position was right but that it was a valid topic of debate within Egyptology.

From that point until 1890, Edwards ran the organization. She was not a field archaeologist. Then in 1890, she left for the United States. On her tour she gave 115-120 lectures. She travelled what could be called today the I-95 circuit speaking to colleges, museums, and learned societies. She observed that there was greater freedom for women in the United States then in the UK. Her previous theatrical experience and operatic training aided in her being able to deliver so many talks.

Unfortunately during the tour she fell and was injured with a compound fracture of left arm. It was the first of three falls and she never fully recovered. The tour became the basis for her next and final book, Pharaohs, Fellahs and Explorers (1892). She died on April 15, 1892.

In the book, she wrote about mounds as a storyteller describing a living being

“He [the Egyptologist] must not only go up the Nile; he must ascend the Great River of Time and trace the Stream of History to its source” (37)

…these wrecks [in Upper Egypt] are noble ruins open to the cloudless sky, and touched with the gold of dawn and the crimson of sunset (40)

… a flood of unexpected light has been cast upon the Biblical history of the Hebrews ; the early stages of the route of the Exodus have been defined (40-41)

In just a little over a decade she had succeeded in her goal.

Her tour of the United States proved successful in expanding the membership of the EEF. After her death, William Copley Winslow, Honorary Secretary of the EEF for the United States, published “The Queen of Egyptology,” in The American Antiquarian stating:

Miss Edwards knew Egypt personally, and its history completely; she mastered the literature of research and exploration… Nay, was she not born to be an Egyptologist…She knew the whole field of Egyptology better than any man… I pray for her, but I never expect to see, another Edwards in the domain of Egyptology. The queenly title is hers. (14:6 1892, 306 and 312)

One might project the Exodus would continue to be a major topic for study among Egyptologists. Multiple articles were published but time does not permit to review them.

Naville, Edouard, “On the Route of the Exodus,” The Journal of the Transactions of the Victorian Institute 26 1893, 12-3.

Gardiner, Alan H., “The Ancient Military Road between Egypt and Palestine,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 2 1920:99-116.

Gardiner, Alan H, “The Geography of the Exodus,” in Recueil d’études égyptologiques dédiées à la mémoire de Jean-François Champollion à l’occasion du centenaire de la lettre à M. Dacier relative à l’alphabet des hiéroglyphes phonétiques, lue à l’Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres le 27 septembre 1822 (Bibliothèque de l’École des hautes études. Sciences historiques et philologiques 234; Paris: E. Champion, 1922), 203-215.

E. Peet, Egypt and the Old Testament (Liverpool: University Press of Liverpool Ltd., 1922).

Naville, Edouard, “The Geography of the Exodus,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 10 1924, 18-39. Gardiner, Alan H, “The Geography of the Exodus: An Answer to Professor Naville and Others,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 10 1924, 87-96.

Vigorous debate by leading Egyptologists over whether the route of the Exodus had been discovered.

With the work of these early Egyptologists, the search for the biblical cities associated with the exodus was on. But it seems that [Alan] Gardiner’s strong condemnation of those whom we might call biblical Egyptologists, continues to cast a pall over serious investigation of biblical history with the aid of Egyptology. Since the 1930s there have been only a few Egyptologists who have integrated their work with biblical studies, in particular as it relates to the exodus tradition. (Gardiner, Alan H, Ancient Israel in Sinai: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Wilderness Tradition, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, 52).

Edwards interest in the Exodus seems to have vanished as well from the record.

[S]he sacrificed a successful writing career to devote herself exclusively to Egyptology and most of all to the cause of rescuing the ancient monuments and archaeological sites so they might be studied before they were totally destroyed. Amelia took up the challenge of alerting the world to the plight of ancient Egypt’s legacy (“Amelia Blandford Edwards, 1831-1892,” Barbara S. Lesko, pamphlet at Brown University).

There was no mention of Edwards’ dedication to finding the route of the Exodus or filling the 430 year gap of the Hebrew sojourn in Egypt.

Similarly on the 140th anniversary of the founding of the EES in 2022. Carl Graves, the Director, The Egypt Exploration Society sent out an email solicitation seeking funds to reprint A Thousand Miles Up the Nile. He wrote that Edwards:

“would inspire generations after her to take up her message to support and promote Egyptian cultural heritage…. That message remains strong and continues to inspire us, the Egypt Exploration Society, to continue her mission.”

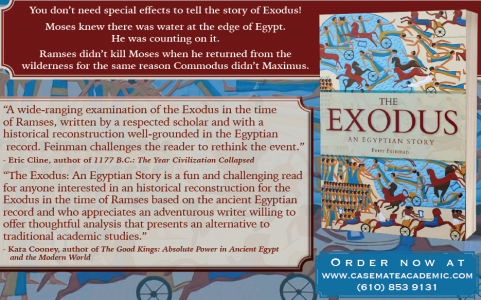

As important as finding the Exodus was at the dawn of Egyptology (as the Bible was at the dawn of Assyriology), the biblical emphasis soon was eclipsed by solely Egyptian concerns. The Exodus subsequently vanished from Egyptology save for some Evangelicals. It had become a subject which no self-respecting Egyptologist would take the Exodus too seriously. We are all familiar with erasure. We know about Hatshepsut and Akhnaton. We see what the National Park Service and the Smithsonian are doing today.

We can add the Egyptological study of the Exodus to that list over what is actually an Egyptian story.