If a picture is worth one thousand words, then a good slogan or branding is for winning an election. Political parties are asked what they stand for, why someone should vote for them, what is their vision for the future.

Such branding needs to be short. No one is going to read a 900+ page party platform even if it will be the governing document for the administration. Think short. Something easy to remember but which packs a punch far in excess of its brevity.

In American history some phases and slogans come to mind as having a powerful appeal.

1600s

We are “as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us” (John Winthrop, 1630)

This lay sermon originally delivered regarding the Puritan city of Boston to which Winthrop was sailing, more or less remained in hibernation until Ronald Reagan. Then it became a bold statement of optimism about the destiny of the United States and its role on this planet.

1700s

“it is a rising and not a setting sun” (Ben Franklin, 1787)

At the close of the Constitutional Convention, this quintessential American voiced these words of optimism over what the Founding Fathers had wrought. The chair Washington sat on as he presided over the convention had an emblem of half of a sun. “Half full or half empty” as we still ask about a glass today. Franklin answered in the positive:

“I have often and often, in the course of the session, and the vicissitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue, looked at that behind the President, without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting: but now at length, I have the happiness to know, that it is a rising and not a setting sun.”

1800s

“Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable,” (Daniel Webster, January 26-27, 1830)

Excerpt from his Second Reply to Senator Hayne (D SC). It was during a time of nullification and the struggle to hold together a country that had recently celebrated its 50th anniversary and its Founding Fathers were dead. It was a defining speech for the second quarter of the 19th century. Although it did not vault him into the White House, it did impress young Mr. Lincoln who did succeed and had a special way with words.

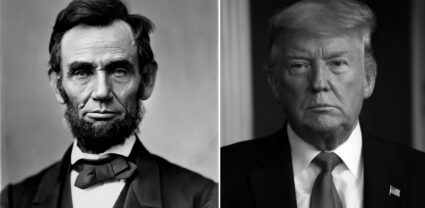

“We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth,” (Abraham Lincoln, December 1, 1862, annual message to Congress).

With, Lincoln, of course there are other memorable phrases which one could choose. Although Lincoln did not refer to the United States as a city on a hill in a passive role that the world is watching. His words were more active as if We the People had been called to a global mission and divine destiny. Despite the carnage all around him and the despair he endured during the Civil War, he remained optimistic about the future of the country.

1900s

In the 20th century, presidents often became better known for the programs that branded their administration.

SQUARE DEAL – Teddy Roosevelt

Roosevelt was no longer president but he hoped to become one again in the upcoming election. After he failed to gain the Republican nomination at the Chicago convention (June 18-22, 1912), he issued this call to action:

“We fight in honorable fashion for the good of mankind; fearless of the future; unheeding of our individual fates; with unflinching hearts and undimmed eyes; we stand at Armageddon and we battle for the Lord.”

As his third party took shape, he delivered his own platform.

“You are taking a bold and a greatly needed step for the service of our beloved country. The old parties are husks, with no real soul within either, divided on artificial lines, boss-ridden and privilege-controlled, each a jumble of incongruous elements, and neither daring to speak out wisely and fearlessly what should be said on the vital issues of the day. This new movement is a movement of truth, sincerity, and wisdom, a movement which proposes to put at the service of all our people the collective power of the people, through their Governmental agencies, alike in the Nation and in the several States….

“Now to you men, who, in your turn, have come together to spend and be spent in the endless crusade against wrong, to you who face the future resolute and confident, to you who strive in a spirit of brotherhood for the betterment of our Nation, to you who gird yourselves for this great new fight in the never-ending warfare for the good of humankind, I say in closing what in that speech I said in closing: We stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord.” (Excerpted from A Confession of Faith, delivered in Chicago, Illinois, August 6, 1912)

NEW DEAL Franklin Delano Roosevelt

FDR responded to his distant cousin’s call in his first inaugural address:

“Only Thing We Have to Fear Is Fear Itself” (March 4, 1933)

A fairly bold and optimistic declaration during a depression. But as with Lincoln during the Civil War, Roosevelt during the depression did not dwell in the carnage or proclaim himself a savior.

FAIR DEAL Harry Truman

NEW FRONTIER John Fitzgerald Kennedy

GREAT SOCIETY Lyndon Baines Johnson

IT’S MORNING IN AMERICA Ronald Reagan

For the optimistic President, America was still a city on a hill.

2000s

“American carnage,” Donald Trump, 2017 inaugural

Going where Lincoln did not go during the Civil War and Roosevelt did not go during the depression, Trump for years has wallowed in the carnage and his role in ending it:

‘This American carnage stops right here and stops right now’

MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN

No “We the People” in sight. No “city on a hill.” No “last best hope of earth.” No “rising sun.”

Perhaps We the People want something better.

I was talking about this the other day with Tim Shriver, the longtime head of Special Olympics, and he remarked to me: “I interact with enough Republicans and Democrats through Special Olympics to know how starved they both are for the country to be pulled back together, so we can do big stuff together again.”

The disunity in the country, Shriver noted, “is literally making people sick and depressed.” Today, he added, “a huge number of Americans have a family member, work colleague or friend whom they are not talking to because of politics.”

It’s just not who we want to be.

“How could it be,” Shriver asked, “that the country that produced an Abraham Lincoln, who, in the middle of a civil war, could utter the words of his second inaugural” — “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds” — “is now a place where the more politically engaged you are today the more you hate your neighbor?”

That’s why, more than anything else now, Shriver argued, “we need leaders and ideas that unite us. A lot of Americans are starving to be part of something larger than ourselves, something that loves us and needs us, like building America together again, solving big problems together again, dreaming big dreams together again.” (Thomas L. Friedman, “It’s Super Wednesday,” March 4, 2020, NYT print)

“People are hungry for a sense of community and unity.” (David Axelrod, “Biden vs. Trump: The General Election Is Here, and Transformed,” September 29, 2020, NYT, print, updated from April 9, 2020 print)

“We need a social vision that is as morally compelling as identity politics but does a better job of describing reality. We need a national narrative that points us to some ideal and gives each of us a noble role in pursuing it. That’s the gigantic cultural task that lies ahead.” (David Brooks, “Why We Got It So Wrong,” Nov. 15, 2024, NYT, print)

What does the Democratic Party stand for?

What is its vision?

MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN: END THE CARNAGE

Who will offer We the People an optimistic vision of a divine destiny?